Antarctica Travel Guide

Welcome to the taste2travel Antarctica Travel Guide!

Date Visited: January 2016

Introduction

There’s no other destination quite like Antarctica – the driest, windiest, coldest, iciest, remotest continent on Earth.

The darkened, rectangular form of a large iceberg stands out against a mountain range in the setting sun.

If you’re looking for a unique travel experience – the journey of a lifetime – then Antarctica is your destination and for many well-travelled souls this is continent number 7 of 7 and a place where most visitors experience a deep sense of awe and respect for the wonder that is ‘mother nature’.

An Adélie penguin on Detaille Island, Crystal Sound, Antarctica.

Travelling to Antarctica requires a little planning and isn’t cheap but the rewards of spending time on the continent cannot be overstated, the space, silence, remoteness and dramatic vistas can be overwhelming at times – it’s an experience that will always stay with you.

Works of ice art – icebergs in the Errera Channel.

Antarctica was the last continent to be explored and is the only continent with no permanent (human) residents, no infrastructure or anything else – it’s 100% raw, unforgiving nature. The continent is not owned by any one country, instead it is governed by a treaty (see the ‘Antarctic Treaty‘ section below).

Emperor penguin’s, such as this one in Crystal sound, have the distinction of being the tallest and heaviest of all penguins.

Everything you require on a trip to Antarctica needs to be carried in from the outside world. The environment is pristine and strict rules placed on tour operators ensure it remains that way – including washing your boots every time you leave the boat for a land excursion. You cannot leave anything on the continent nor can you remove anything – not even a small pebble from a beach.

An afternoon Zodiac sea excursion on Crystal Sound. Each day of our trip we did two excursions, sometimes a sea excursion or a land excursion.

From towering peaks, pristine ice-filled bays, massive calving glaciers, icebergs, penguins, seals, whales and birds the scenery and wildlife of Antarctica is nothing short of astounding. If you are a keen photographer, my advice is to carry ample spare memory cards for your camera – I took about 7,000 photos during my two-week trip.

An iceberg illuminated against the sky of a setting sun.

One guarantee with a trip here is that each day, just when you think it can’t get any grander or any more spectacular – it does. Antarctica is awe-inspiring and humbling. There is a magic in the cool, crisp air – a magic that will always remain with those fortunate few who get to travel here.

Gentoo penguins, travelling along a Penguin highway on D’Hainaut Island

Location

A satellite view of Antarctica.

Antarctica is located at the bottom of the world at the South Pole and is surrounded by the Southern Ocean.

Over 98% of Antarctica is covered by ice and it has the distinction of being the driest and coldest continent on earth. Beneath all that ice is a sizeable landmass which makes Antarctica the fifth largest continent on earth.

History

Remnants of an old whaling boat surrounded by whale bones on D’Hainaut Island.

The term Antarctic was first used in the 2nd century AD and refers to the “opposite of the Arctic“.

The existence of a vast southern continent, named Terra Australis, was based on a centuries-old theory that the land mass in the Northern Hemisphere must be balanced by a large land mass in the Southern hemisphere.

The first person to cross the Antarctic circle was explorer Captain James Cook in 1773. He explored islands close to Antarctica but never sighted the continental landmass.

Instead Cook sailed on to discover Australia and in the early 1800’s the British (believing there could be no other great southern landmass) named Australia – Terra Australis.

In the 1820’s several expeditions claimed to have sighted the Antarctic ice shelf and in 1821, an American sealer – John Davis – claimed to be the first person to set foot on the continent. In the 1890’s Norwegian whalers set up whaling camps, the remains of which can still be seen today on various beaches.

In the early 20th century, during a period known as the ‘Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration‘ different countries launched expeditions to the continent with many focused on one goal – to be the first to reach the South Pole.

The Norwegian, Roald Amundsen, was the first person to reach the South pole on December 14, 1911 – narrowly beating an expedition led by Englishman – Robert Falcon Scott.

One of the principal figures during this period was Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton whose first exposure to Antarctica was as an officer on Scott’s expedition in 1901.

Shackleton led three British expeditions to Antarctica, with the most ambitious being the last – an attempt to cross the continent from sea to sea. This failed when his ship, Endurance, became stuck in pack ice.

An American – Richard E. Byrd – was the first person to fly a plane over the South Pole in 1929.

Today scientists from more than 25 countries inhabit research bases on the continent.

Antarctic Treaty

The flag of Antarctica flies on the bow of our expedition ship – the Ocean Diamond.

In 1959, twelve countries (who at the time were actively using Antarctica for scientific research purposes) came together in Washington DC to sign the Antarctic Treaty.

Today, 53 countries are signatories to the treaty, the main articles of which are:

- Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only (Art. I)

- Freedom of scientific investigation in Antarctica and cooperation toward that end … shall continue (Art. II).

- Scientific observations and results from Antarctica shall be exchanged and made freely available (Art. III).

While certain countries maintain territorial claims over parts of Antarctica, Article IV states:

“No acts or activities taking place while the present Treaty is in force shall constitute a basis for asserting, supporting or denying a claim to territorial sovereignty in Antarctica or create any rights of sovereignty in Antarctica. No new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim to territorial sovereignty in Antarctica shall be asserted while the present Treaty is in force.”

Antarctica is rich in mineral resources, which many countries are keen to exploit. While the treaty maintains the current status quo, it is set to expire in 2048.

Antarctic Blues

“Antarctica Blues” – an iceberg in Crystal Sound.

Antarctic landscapes tend to be very monochrome, with white, grey and black being the predominate colours.

The blue glow of an iceberg in Crystal Sound provides a splash of colour in the otherwise monochrome Antarctica.

Interrupting this monotonousness are the spectacular splashes of Antarctic blue which can be seen in the many glaciers and icebergs.

The shades of blue in Antarctica, such as in this iceberg in Crystal Sound, are dazzling.

The striking blue tone is caused when light enters ice – the red (long wavelengths) part of white light is absorbed by ice and the blue (short wavelengths) light is transmitted and scattered, often creating spectacular, dazzling scenes of Antarctic blues.

An iceberg glowing in the morning sun in the Graham passage. The dimpled effect is caused by water action when the iceberg is below the waterline.

Antarctic Tartan

My Antarctic tartan scarf, which I purchased at the Port Lockroy post office.

Yes! Antarctica has its own tartan which was designed at the other end of the world in Scotland.

The colours used in the design are representative of colours found on the continent – white represents snow, ice and ice floes; grey represents the rocks and towering granite peaks and the seals; yellow represents penguin plumage and the different shades of blue represents the crevasses in the sea, glaciers and icebergs.

The scarves are sold at the British-run Port Lockroy Post Office (see ‘Day 7‘ below).

Apart from the ships gift shop – the PO was the only shopping opportunity in Antarctica.

Currency

There is no Antarctic currency! All expenses on the ship were billed to my credit card while the Port Lockroy post office accepted Credit cards, U.S. dollars, Pound Sterling and Euro.

When to Go

Our first blue skies in Antarctica came on the afternoon of day 7 while cruising through the stunning Lemaire channel.

The shades of blue in Antarctica, such as in this iceberg in Crystal Sound, are dazzling. Travel to Antarctica is restricted to spring/ summer (October to March), when daylight lasts between 18 and 24 hours each day.

Even in summer, we were subjected to blizzards, days of overcast, freezing weather and generally bleak conditions. But when the sun does shine, Antarctica is sublime!

Visa Requirements

A souvenir Antarctica passport stamp, which is issued by the post office at Port Lockroy.

Since no country owns Antarctica, no visa or even a passport is required to visit. However, you will need your passport in order to gain entry to the country where you end your expedition. The British post office at Port Lockroy offers a cute souvenir passport stamp.

Getting There

Located at 54° South, Ushuaia is the most southern city in the world and, due to its close proximity to the southern continent – the departure point for boat trips to Antarctica.

Despite its remote location and harsh environment, there are plenty of tour companies who offer paying guests the opportunity to join comfortable ‘expedition’ ships which sail from the world’s most southern city (Ushuaia, Argentina).

There are no facilities anywhere in Antarctica so your ship serves as your floating world during your journey – the only time you leave the ship is twice a day for excursions.

Quark Expeditions

I chose to travel with Seattle-based Quark Expeditions who were very professional, extremely well organised and generally provided a very smooth travel experience. I would highly recommend them.

I contacted their office last minute and secured a berth in a shared 3-bed cabin on their 14-day “Crossing the Circle” expedition which is Quarks most southern expedition, crossing the Antarctic Circle at 66°30′ S. Most trips to Antarctica do not venture as far south as the circle.

Quark Expeditions brochure map for their Crossing the Circle expedition.

The cost of the trip in a shared triple room was US$9,000. If you require more privacy you will need to pay much more – up to $15,000. Everything was included in the price, except for alcoholic beverages, and any additional activities you wished to do. I added a night of camping which cost an additional US$250 – how often will you have the opportunity to camp on Antarctica?

Quark Expeditions’ Ocean Diamond, moored in the incredibly beautiful Graham passage.

My home in Antarctic was the Ocean Diamond, which Quark describe as a modern, stable, super-yacht and, with its twin stabilisers and an ice-strengthened hull, the ship is ideal for a trip to Antarctica.

Returning to Quark Expeditions’ Ocean Diamond after a Zodiac sea excursion on Crystal Sound.

The ship features 100 suites, accommodating up to 189 passengers, with 100 crew members on board from three different teams:

- Ship Crew – The crew included our Russian Captain, other officers and a host of Filipinos who took care of the operational side of the ship.

- Hotel Crew – Headed up by a competent German manager, the hotel crew was comprised mostly of Filipinos who took care of the cabins, served up amazing ‘5-star’ multi-course meals three times a day (many people gained weight) and manned the bar into the wee hours.

- Expedition Team – The expedition team was headed up by ‘Woody‘, an Australian who has many years of polar experience – both in the Arctic and Antarctic. The team included scientists, biologists, geologists and other specialists from a host of countries who gave daily presentations on the flora, fauna, geology and history of Antarctica. Twice a day we would leave the ship to do either sea or land excursions with a member of the expedition team piloting a zodiac.

An Adélie penguin on Detaille Island, Crystal Sound, Antarctica.

For those who would rather not cross the rough Drake Passage by ship – or are short on time – Quark offer ‘Fly/ Cruise voyages‘ where you can either fly both ways (flights depart from Punta Arenas in Chile) or fly one way/ sail one way.

Itinerary

My map of Antarctica, showing the route of our expedition.

An interactive Google map of the places visited during my 14-day journey to Antarctica:

Day 1 to 3: Ushuaia to Antarctica

Our Quark Expedition ship, the Ocean Diamond, departing from Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina.

The first part of the journey towards the bottom of the world was a relaxing sail through the narrow Beagle Channel, from the port of Ushuaia, to the Southern Ocean, and the roaring Drake Passage.

Once in the Drake passage, and after being fore-warned to make the ship ‘Drake-proof‘, we set a direct course south to the Antarctic Circle.

The Drake passage is notorious for rough crossings – our crossing lasted 77 hours.

The journey to the Antarctic circle, which lies 1,370 km south of Ushuaia, took 77-hours, with the boat heaving in heavy seas, across the infamously rough Drake passage, most of the way.

While seas in the “Roaring 40s” are rough, the Drake passage lies in the even rougher “Screaming 50s”. At this latitude, there are no landmasses to interrupt the flow of currents and mountainous seas, with constant, fierce winds, whipping the Southern Ocean into a turbulent frenzy.

The Drake passage has only two temperaments: “the Drake Shake” or “the Drake Lake.” More often than not it’s the former, with the ships’ windows quickly resembling a washing machine window due do the constant froth of high waves.

The bridge of Quark Expeditions ‘Ocean Diamond’ was almost always open to passengers.

One of the best places to watch the rough seas of the Drake passage was from the elevated safety of the bridge of the ‘Ocean Diamond’, which was open to passengers for almost the entire journey.

Thanks to the giant on-board stabilisers, the journey was smoother on the Ocean Diamond than it would have been on other boats, however, due to sea-sickness, 70% of passengers remained in bed during the crossing of the passage.

A ‘sunset’ view at 11 pm, near the Antarctic Circle, north of Adelaide Island.

After 77-hours of heaving seas, we had entered the much calmer waters of the Bellingshausen Sea, which lies on the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula. We were now on approach to our first destination, the Antarctic Circle, which lies at 66°30′ S.

Most trips to Antarctica do not venture so far south, with our trip requiring 14 days rather than the standard 10 days, in order to allow time for the extra distance travelled.

Everything in Antarctica is weather dependent, with nothing guaranteed, including reaching one of our main goals – the Antarctic Circle. Crossing the circle (or even getting near it) isn’t always possible and is dependent on sea-ice conditions at the time.

The view at 2 am near the Antarctic Circle, north of Adelaide Island.

At such southern latitudes, the seas are often blocked by icebergs, ice floes and pack ice. A decision on whether it’s safe to proceed further south could only be made by the captain once he assessed the icy conditions.

The waters surrounding Adelaide Island are full of large icebergs and smaller ice floes.

Luckily for us, our skilled captain was able to slowly navigate around the numerous icebergs so that we could reach our goal.

Day 4 – AM: Antarctic Circle near Adelaide Island

A group photo, taken at the Antarctic Circle, one of the major goals on our Crossing the Circle expedition.

After many hours of slow, careful manoeuvring, our Russian captain had steered the Ocean Diamond to our first goal, delivering us, safely, to the Antarctic Circle – the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of planet Earth.

Shortly before 5 am on day four, our expedition leader, Woody, woke the ship with the exciting news that we would shortly cross the Antarctic circle and invited us to join the crew on deck to drink a celebratory toast of champagne.

Even for the crew members, this was exciting. For many, it was also their first time to cross the circle, with most trips never venturing so far to the south.

A GPS device confirms we have crossed the Antarctic Circle, which lies at 66°30′ S.

South of the Antarctic Circle, the sun is above the horizon for 24 continuous hours, at least once per year, during the summer solstice, while it is below the horizon for 24 continuous hours, at least once per year, during the winter solstice.

A cause for celebration as few travellers get to cross the Antarctic circle.

Day 4 – PM: Adelaide Island

The Ocean Diamond moored offshore from Adelaide island.

After crossing the circle, we attempted to push further south to Marguerite Bay but unfortunately ice conditions worsened, blocking our way, so the captain anchored off Adelaide Island to allow us to do a sea excursion – our first time off the ship since leaving Ushuaia.

After our 77-hour crossing of the Drake passage, this was our first sighting of a Crabeater seal during our sea excursion off Adelaide island.

During the excursion we photographed amazing icebergs and saw our first Crabeater seals (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information) lazing around on ice floes.

Crabeater seals, such as this one at Adelaide Island, are hunted by Leopard seals and Orca whales, who prey on them by bumping them off ice floes.

Thanks to their thriving population, the Crabeater seal is a common sight in Antarctic and we would see many in the coming days.

A Crabeater seal lazes on an ice floe near Adelaide Island.

After our afternoon excursion, the ship sailed north, away from the heavy ice conditions, and towards the protected waters of Crystal sound.

Day 5 – AM: Crystal Sound and Detaille Island

The breath-taking scenery of Crystal Sound as seen from Detaille Island.

On the morning of day 5 we awoke to the spectacular scenery of Crystal Sound. The sound was named by the UK Antarctic Place-Names Committee in 1960 because many features in the sound are named for men who have undertaken research on the structure of ice crystals.

A Kelp Gull on Detaille Island, Antarctica.

This morning we would visit the famed ‘Base W‘ on Detaille Island, a former British research station which is a perfectly preserved time capsule of Antarctic life from the 1950s.

Located on Detaille Island – Base W is a former British research station which is now a museum.

Due to the fact that visitor numbers inside the small hut are limited, we were divided into two groups with each group taking it in turns to do one of two excursions:

- Detaille Island visit.

- Zodiac excursion around Detaille Island.

Detaille Island Visit

Skies and a coat remain on the racks in the entrance of Base W on Detaille Island.

Located on Detaille Island, Base W was established in 1956 as a British research station, primarily for survey, geology and meteorology and to contribute to the International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957. The base consisted of a hut and associated structures, including a small emergency storage building.

Books remain on the shelf at Base W on Detaille Island.

After opening the Olympic games in Melbourne in 1956, the Duke of Edinburgh, who was conducting a tour of British Antarctic bases, visited Base W. As home to the Antarctic Tennis Club, it was only fitting that the Duke played a game of tennis while visiting the base.

Base W on Detaille Island serves as a reminder of life in Antarctica in the 1950s.

In 1958 the base was hastily abandoned due to bad weather, with the occupants instructed to leave everything behind.

Located on Detaille Island, Base W was used for a few short years as a British research station.

As a relatively unaltered research station of the late 1950s, it provides a reminder of the science and living conditions that existed when the Antarctic Treaty was first signed in 1959. It’s a time capsule literally frozen in time.

Unopened bottles of sauce remain in the kitchen cupboards at Base W on Detaille Island.

Today, the base is a perfectly preserved, with kitchen cupboards stocked with provisions, clothes still hanging on their hangers and books arranged on bookshelves – all of it perfectly preserved by the dry, freezing Antarctic air.

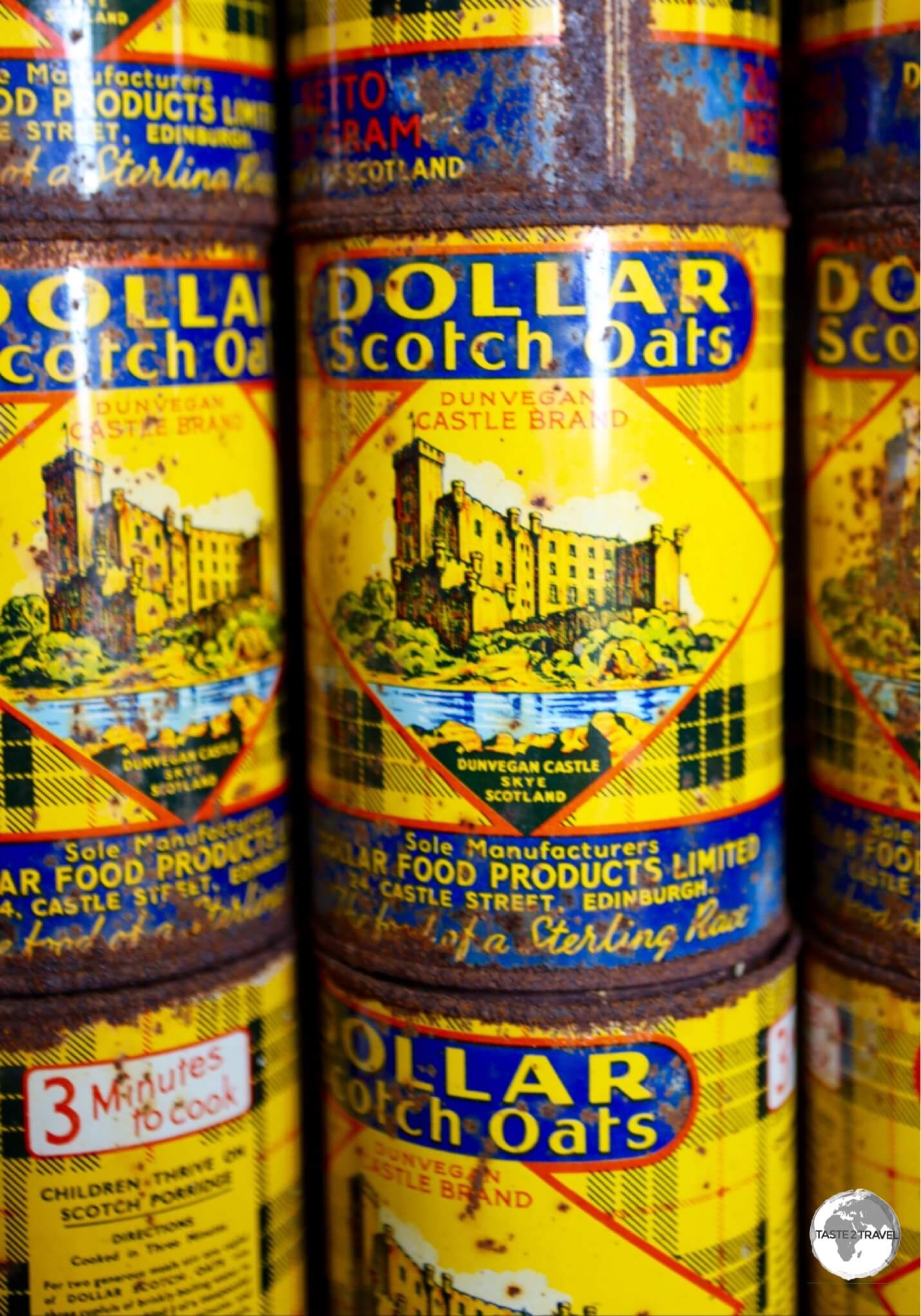

Cans of oats remain on the kitchen shelf at Base W on Detaille Island.

It all felt as if the occupants left just yesterday. A fascinating insight!

From thermal pants to magazines, the living quarters at Base W, on Detaille Island, remain undisturbed since the late 1950s.

Remote and unattended, the hut is never locked but visitors are requested to sign the visitors’ book and to touch nothing!

Scientific research material and log books remain on the desk in the office at Base W, Detaille Island.

Zodiac Excursion around Detaille Island

An Adélie penguin on Detaille Island strikes a pose.

During the Zodiac excursion, we had our first encounter with a group of Adélie penguins (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information) who had congregated on an ice ledge on the southern side of Detaille Island.

The Adélie penguins, which are the most southerly distributed of all penguins (along with the Emperor penguin), are named after Adèle Dumont d’Urville, the wife of French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, who first discovered the penguin in 1840.

An Adélie penguin, airing its flippers on Detaille island.

Adélie penguins feed on tiny aquatic creatures, such as shrimp-like krill, but also eat fish and squid. They have been known to dive as deep as 575 feet in search of such quarry, though they usually hunt in far shallower waters less than half that depth.

Adélie penguins, such as this one on Detaille Island, obtain their food by both predation and foraging, with a diet of mainly krill and fish.

Like other penguins, Adélie penguins are sleek and efficient swimmers, travelling hundreds of kilometres, round-trip, to procure a meal. When diving for food, Adélie penguins can hold their breath for up to six minutes and frequently reach depths of 150 metres.

Adélie penguins on Detaille Island.

Male and female Adélie penguins are a very similar size and have very similar features, which makes it hard to tell the difference between them. They sport a characteristic ‘tuxedo’ look, with a black back and head, white chest and belly, and white rings around the eyes.

Day 5 – PM: Crystal Sound

The towering, majestic peaks of Graham Land line the shore of Crystal Sound.

Following our morning excursion to Detaille Island, we remained in the incredibly scenic Crystal Sound where we did an afternoon Zodiac sea excursion, with the towering peaks of Graham Land providing an awe-inspiring backdrop.

Zodiac cruising between icebergs on Crystal Sound.

Crystal Sound (66°23′S 66°30′W) is a channel between the southern part of the Biscoe Islands and the coast of Graham Land. Named after the area being used by scientists for research on ice crystals, it is a truly stunning place to see snow-covered mountains, floating icebergs and crystal-clear water as far as the eye can see.

The dimpled, exposed underside of a turned iceberg in Crystal Sound.

During the excursion, we saw many different shades of Antarctic Blue ice, with the occasional chunk of glassy blue, Glacial ice, floating among the milky-coloured icebergs.

Glacial ice often appears blue when it has become very dense and free of bubbles. Years of compression gradually make the ice denser over time, forcing out the tiny air pockets between crystals. When glacier ice becomes extremely dense, the ice absorbs a small amount of red light, leaving a glassy, bluish tint in the reflected light, which is what we see.

The translucent blue of a large chunk of pure water glacial ice floating in Crystal Sound.

Glacial ice in Antarctica can be up to 1,000,000 years in age, forming the purest source of water on planet Earth. During one excursion, a crew member retrieved a piece of glacial ice which was then allowed to melt into a special presentation bottle, which was then auctioned off at the end of the trip. A precious souvenir from a pristine world!

An Emperor penguin in Crystal Sound.

One of the highlights of the excursion was the spotting of a small group of Emperor Penguins (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information), who were looking less-than-majestic as they were undergoing their annual Catastrophic moult.

Emperor penguins in Crystal Sound still bearing the fluffy feathers from their annual Catastrophic Moult.

These were the only Emperor penguins we saw during our 14-day trip. The Emperor penguin has the distinction of being the tallest and heaviest of all penguins.

A Catastrophic Moult

Emperor penguins in Crystal Sound slowly shedding their old feathers during their annual Catastrophic Moult.

Like all other penguin species, Emperors go through a moulting process. This happens once a year and is referred to as a Catastrophic Moult due to the fact that all their feathers are replaced at once.

The new feather grows under the old one, pushing it out. The old feather does not fall out until the new one is completely in place. The process lasts about two weeks and during this time they must remain on land as their feathers are not waterproof during the process.

Since they feed on fish they are on an enforced ‘fast’ until they can return to the sea.

During our trip we were very fortunate to see one small group of Emperor’s who were going through this awkward process. Why awkward?

The moult is patchy and can give penguins a scruffy look – it’s not always pretty! Then there’s the waiting around – two weeks on land. However – it allowed us to observe this rarely seen penguin at close quarters – and you know something is special when the crew are just as excited as the passengers.

A Zodiac provides a sense of scale for this huge female Southern Elephant seal in Crystal sound.

Another highlight of our sea excursion was the sighting of our first Southern Elephant seal, a huge adult male (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information) who was relaxing on an ice floe.

The largest of all seals, these blubbery giants can weigh up to 3,600 kilos (8,000 lb) and grow to 4.5 metres (15 ft) in length.

A huge adult female Southern Elephant seal resting on an ice floe in Crystal sound.

What’s even more impressive is their diving ability. Southern elephant seals can dive from 400 to 1,000 metres (1,300 to 3,300 feet) for up to 20 minutes at time. The deepest recorded dive doubled that average, reaching a little over 2,100 metres (6,890 feet) deep.

In between hunting for Krill, Crabeater seals like to unwind on ice floes such as this one in Crystal Sound.

As with all other sea excursions, we saw many Crabeater seals, relaxing on ice floes after feeding on krill. With an estimated population of 75,000,000 – the Crabeater seal is, by far, the most abundant seal species in the world and breeds around the entire coastline of Antarctica.

Due to their diet of krill, Crabeater seals, such as this one in Crystal sound, often have a blood-red stain around their mouths.

Due to their diet of krill, Crabeaters seals often have a blood-red stain around their mouths. Despite its name, Crabeater seals do not eat crabs. Early whalers assumed the red stain around their mouths was from eating crabs, hence their name.

Day 6 – AM: Yalour Islands

The Ocean Diamond, moored against a large chunk of ice, on a stormy day, in the Yalour Islands.

Overnight, the Ocean Diamond sailed north, and into a storm, crossing back over the Antarctic circle, to our next destination – the Yalour Islands (65º14´00´´S, 64º10´00´´W), a small group of islands and rocks in the Southern part of the Wilhelm Archipelago.

We awoke to a raging blizzard, which is par for the course during summer in Antarctica, and, after breakfast, embarked on our morning Zodiac sea excursion to view the Adélie Penguins.

A raging blizzard envelopes an Adélie penguin breeding colony on one of the many rocky islets of the Yalour Islands.

Located just 2 km offshore from the imposing peaks of Graham Land, the Yalour Islands are home to about 8,000 pairs of Adélie penguins who have established their breeding colonies on tiny, rocky islets.

An Adélie penguin feeding its chick’s, during a raging blizzard, on the Yalour Islands.

The penguins had just given birth to their fluffy chicks, who clearly were not appreciating the freezing, wet conditions, especially since they have fluffy down feathers, which are not as water repellent as the feathers of adults.

Small in area, the Yalour Islands are comprised of many small rocky, igneous islets which are home to numerous Adélie penguin breeding colonies.

There were lots of new-born chicks present, who were huddled together to maintain body warmth and protect themselves (their feathers are not waterproof at this stage) against the driving snow.]

This Crabeater seal in the Yalour Islands bears the battle scars from a previous encounter with a predatory Leopard seal.

Day 6 – PM: Petermann Island

A Gentoo penguin colony on Petermann Island is dwarfed by the imposing peaks of Graham Land.

From the Yalour Islands, we cruised a short distance north, to our next destination, Petermann Island (65°10′33″S 64°08′10″W), a small island which was discovered by a German expedition of 1873–74, who named it after geographer August Petermann.

The island sits in the shadows of the towering igneous peaks of Graham Land, which is the name given to this part of the Antarctic mainland.

A huge female Southern Elephant seal, resting in front of the Argentine Groussac Refuge on Petermann Island.

Following lunch, we made an afternoon land excursion to Petermann Island, landing at Port Circumcision, which was named by a French expedition who discovered the port on the 1st of January 1909, the traditional day for the Feast of the Circumcision.

The port is home to an Argentine refuge hut Groussac Refuge, which was surrounded by breeding Gentoo penguins. Also claiming a large piece of real estate was a huge adult female Southern Elephant seal who, more than once, almost squashed a wandering Gentoo penguin.

South Polar Skuas fighting on Petermann Island.

Petermann Island is also an important breeding ground for the Petermann Island South polar skua (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information).

The South polar skua, which is much larger than its northern hemisphere cousin, is very curious, playful, daring and mischievous.

While it feeds mainly on fish, which it often obtains by robbing other birds of their catch, the skua will also attempt to pluck young penguin chicks from their nests.

Our talented Zodiac pilot, getting us ready to depart from Petermann Island to return to the Ocean Diamond.

Day 7 – AM: Damoy Point

Zodiac cruising around Damoy point with the Ocean Diamond moored in the Neumayer Channel.

On the morning of day 7, with the sun trying hard to finally make an appearance, the plan after breakfast was to make a land excursion to Damoy point (64º49´00´´S, 63º31´00´´W) which is a rocky isthmus off the west coast of Wiencke Island.

Our ship dropped anchor in the narrow Neumayer Channel which weaves its way between the glacier-clad shoulders of Anvers and Wiencke Island.

Two Crabeater seals relaxing on an ice floe at Damoy Point.

Wiencke Island is the southernmost of the major islands of the Palmer Archipelago, a group of islands which lie off the north-western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

An interesting ice formation on an iceberg at Damoy Point.

Located near Damoy point, Dorian bay is home to a former British scientific base, Damoy Hut, which still contains scientific equipment and other artefacts. Also nearby is an Argentine refuge hut Refugio Bahia Dorian, which was constructed in 1957.

A wind-sculptured Iceberg, sitting in the Neumayer channel at Damoy point.

The original plan was for us to land a Dorian bay and visit the British hut, however, due to dangerous ice conditions in the bay, the plan was abandoned and instead we made a Zodiac sea excursion around Damoy point.

Gentoo penguins have established a small breeding colony around a marker on Casabianca Island, which lies 1 km offshore from Damoy point.

Cruising the Neumayer channel at Damoy point with our Zodiac pilot who was also one of the Expedition crew specialists.

Day 7 – PM: Goudier Island (Port Lockroy)

Base A – aka Bransfield house – at Port Lockroy.

Our next destination was Goudier Island (64°50′S, 63°30′W) which is located on the southern side of Damoy Point – just 800 metres south of Dorian bay. After 10 minutes at sea, we had arrived at our next destination!

This flat, stony island, which lies off the coast of Wiencke Island, is home to the British – Base A – which is located at Port Lockroy, the only place in Antarctica where you can shop!

The former sleeping quarters at Base A are now part of the museum displays inside Bransfield house, Port Lockroy.

Originally established, in 1944, as a research base, Base A was the first permanent British base to be established on the Antarctic Peninsula. The base was closed in 1962 when operations were transferred to another station.

The former kitchen of Base A is a highlight of the museum at Bransfield house, the former British base at Port Lockroy.

The base, which is housed in the historic Bransfield house, was renovated in 1996 and is now one of the most popular tourist attractions in Antarctica, offering the only gift shop and post office in Antarctica.

Artwork on the wall at Base A at Port Lockroy, which dates from the 1960’s, depicts British actress Diana Dors, who was often compared to Marilyn Monroe.

Proceeds from the shop are used to maintain the museum operations. The post office, which issues souvenir Antarctica passport stamps, has the distinction of being the most southerly post office in the world.

The property is managed by the United Kingdom Antarctic Heritage Trust, who are responsible for other historic sites in Antarctica, Including Base W on Detaille Island.

The Nissen hut at Port Lockroy provides accommodation for the four volunteer staff members who operate the base during the summer months.

During the summer season, Port Lockroy manned by four volunteers who live in a Nissen hut at the rear of Bransfield house. There are no showers at the base so the volunteers came aboard our ship to use our shower facilities.

A Gentoo penguin at Port Lockroy.

When not attending to passing tourists, the volunteers at Port Lockroy are tasked with monitoring the numerous Gentoo penguin population which breeds on the island.

A curious Gentoo penguin at Port Lockroy.

Gentoo’s are easily identified by their orange-red coloured becks, which offer a rare splash of colour in the otherwise monochrome Antarctica.

Gentoo penguins, such as this one at Port Lockroy, have peach-coloured feet.

With flamboyant red-orange beaks, white-feather caps, and peach-coloured feet, Gentoo penguins stand out against their drab, rock-strewn Antarctic habitat.

A male Gentoo penguin at Port Lockroy seeks ‘favour’ from a female by offering her a pebble for her nest.

Gentoo parents, which often form long-lasting bonds, are highly nurturing. At breeding time, both parents will work to build a circular nest from stones.

The rituals associated from nesting are often comical with males at Port Lockroy seeking ‘favour’ from females by offering pebbles to help build their nest. Often those pebbles have been stolen from a neighbouring nest!

Gentoo Penguins at Port Lockroy, sitting on their nests.

Once the next is complete, the mother deposits two spherical, white eggs, which both parents take turns incubating for more than a month. Hatchlings remain in the nest for up to a month, and the parents alternate foraging and brooding duties.

A Gentoo penguin at Port Lockroy, drying its flippers after exiting the sea.

Widely spread throughout Antarctica, the Gentoo’s are the penguin world’s third largest members, reaching a height of up to 90 cm (30 inches) and weighing in at 5.5 kg (12 lb).

Lemaire Channel

A view of the towering peaks of Graham Land from the narrow Lemaire channel.

After visiting Port Lockroy, we continued our meander north, passing through the breath-takingly, beautiful Lemaire channel, which is 11 km long and 1,600 metres wide at its narrowest point.

The narrow Lemaire channel is lined with gigantic glaciers and vertical granite peaks and ridges.

Wedged between Kiev Peninsula in the mainland’s Graham Land and Booth Island, the protected waters of the channel are a highlight of Antarctica, offering stunning panoramas in every direction.

A view of the impossibly vertical Antarctic mainland – Graham Land – from the Lemaire channel.

Day 8 – AM: Paradise Bay and Neko Harbour

The view of Paradise bay, and the mountainous, glacier-covered Antarctic Peninsula, from Base Brown.

On the morning of day 8 we awoke in the stunningly beautiful Paradise Bay which is a large sea inlet, located south-west of Andvord Bay and Neko harbour.

The morning excursion would comprise two parts; a land excursion to the Argentine Base Brown, followed by a zodiac sea excursion around Neko harbour.

A Gentoo penguin on an ice floe in Paradise bay.

For myself, and many other passengers, this landing would be significant in that it would allow us to visit our 7th (of 7) continent.

Thanks to its location on the Antarctica continent and its relatively mild weather, Base Brown is a popular place for stepping onto the 7th continent. In all other places, we landed on offshore islands.

A visit to the Argentine Base Brown, in Paradise bay, allowed us to finally step ashore the continental landmass of Antarctica.

Located along the harbour’s deep-water coast lies the small Sanavirón Peninsula, a rocky promontory which is home to Base Brown, an Argentine base which is manned during the summer months.

A view of Paradise bay and the Ocean Diamond from Base Brown.

Named after Almirante Brown (Admiral Brown), the father of the Argentine Navy, the base was burned to the ground by the station’s doctor on 12 April 1984 after he was ordered to stay for the winter.

The base lies 1,100 km (680 mi) from Ushuaia, the nearest port.

A rare sight in this frozen, white land – green moss covers the ground at Base Brown, in Paradise bay.

Due to its milder climate, green moss grows on the ground at Base Brown, offering a rare splash of colour in the, otherwise monochrome, Antarctic landscape.

An Antarctic tern, flying over Base Brown in Paradise bay.

The base is home to a large Gentoo penguin colony, which allowed for (yet more) entertaining photos, with numerous seabirds also nesting on the mossy ground.

Our Zodiacs provide a sense of scale for the imposing glaciers of Andvord bay.

After visiting Base Brown, we did a Zodiac sea excursion around Andvord bay which is lined by imposing, towering glaciers which regularly calve, sending chunks of ice, some the size of large buildings, plunging into the bay.

Due to the risk of sudden tidal waves caused by falling ice, we were required to keep a safe distance from the ice cliffs which are hundreds of metres tall.

An iceberg in Neko harbour has been artfully carved by sea water.

Andvord bay lies within the much larger Neko harbour, which is full of interesting icebergs and ice floes.

Day 8 – PM: Danco Island

A view of the ice-filled Errera Channel from Danco island.

On the afternoon of day 8, we continued north, passing through the Errera Channel, eventually reaching Danco Island (64º44´00´´S, 62º36´00´´W) which was basking in glorious sunshine.

A view of the Errera channel, and the mountainous Antarctic peninsula, basking in glorious sunshine near Danco Island.

The island, which is 2-km in length, is located in the southern part of the Errera Channel, offshore from Graham Land, and close to Neko Harbour.

A view of the Antarctic peninsula (Graham Land) and the Errera channel from Danco Island.

The island was named for Emile Danco (1869–1898), a member of Gerlache’s 1898 Belgian expedition, who died after becoming trapped in ice.

A view of the Errera channel, Graham Land and a large Gentoo penguin colony from Danco Island.

We landed on the north shore of the island, which is the site of a wide, flat, cobbled beach.

A Gentoo penguin, with her chick’s, at the busy breeding colony on Danco Island.

From the beach, a trail leads up a slope to a ridge which provides panoramic views of the mainland (Graham Land), the Errera channel and a very large, smelly, and noisy, Gentoo penguin colony, where adults were busy feeding their new-born chicks.

A Gentoo penguin feeding its chick’s on Danco Island.

Camping at Leith Cove

Armed with five different layers of clothing, I’m ready for a night of camping under the stars at Leith cove, a truly spectacular campsite.

On the evening of day 8, those lucky souls who paid for a night of camping on Antarctica were taken by zodiac to the relatively sheltered Leith cove (64°52′S 62°50′W), which lies in the north-east of Paradise Harbour, along the west coast of Graham Land.

It’s believed the cove was named by Scottish whalers after the town of Leith, which was the hometown of the whaling company, Salvesen and company. Situated in the cove is a small island, which rises to about 40 metres above sea level, which would be our campsite for the night.

The island is surrounded by a small channel which separates it from the mainland which is characterised by towering ice cliffs and glaciers.

After digging a trench and laying out my bivouac, my frigid campsite at beautiful Leith cove was ready for a night sleeping under the stars on Antarctica.

After receiving some instructions, we dug ourselves a ditch in the snow, laid out our bivouacs and tried to sleep! During the night, the sound of constantly howling wind was punctuated by the sounds of calving glaciers, with large chunks of ice plummeting into the channel around the island.

Wrapped up and protected against the elements, ready for my night of camping on Antarctica.

Tents are not an option and not really needed (provided you dig your ditch deep enough). Despite the cold (I slept in 5 layers of clothing), it was a beautiful, unforgettable experience. How often will you have the opportunity to sleep on the frozen continent?

Day 9 – AM: Cuverville Island

A Gentoo penguin colony on Cuverville Island, with the Ocean Diamond moored in the Errera Channel.

On the morning of day 9 we made a land excursion to Cuverville Island (64º41´00´´S, 62º38´00´´W) which stands at the entrance of the Errera channel.

A Weddell seal, relaxing on the beach at Cuverville Island.

Cuverville Island was discovered by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899) under Adrien de Gerlache, who named it for Jules de Cuverville (1834–1912), a vice admiral of the French Navy.

An adult Gentoo penguin with two chicks on Cuverville island.

Measuring 2 km by 2.5 km, Cuverville Island is a steep-sided dome, two-thirds of which is covered by a permanent ice-cap. The island was used as a whaling base in the early 20th century, with various whaling artefacts, including bones and a whalers’ boat, scattered on the beach.

A mischievous South polar skua on Cuverville Island, trying to steal one of our warning flags.

We landed on a cobblestone beach on the northern shore of the island, from where we climbed a steep slope which afforded panoramic views of the Errera channel and a large Gentoo penguin colony.

A Gentoo penguin, fending off an attack by a predatory South polar skua on Cuverville Island.

Apart from breeding Gentoo’s, Cuverville Island is home to Antarctic terns, Cape petrels, Kelp gulls and the very mischievous, and predatory, South polar skua, which harass Gentoo chicks and play with anything left lying around.

Day 9 – PM: Wilhelmina Bay

A Humpback whale diving in Wilhelmina (aka ‘Whale-mina’) bay.

On the afternoon of day 9, we sailed into the spectacular Wilhelmina Bay, which is known as the place for whale watching in Antarctica, especially Humpback whales, which gather in pods to feed.

With soaring (2,000 metre+) mountains on both sides of the bay, and an inaccessible shoreline covered with towering ice walls, glaciers and snow, this sheltered, and stunningly beautiful, bay is a preferred feeding ground for the majestic Humpback.

Getting up close! The whale watching at Wilhelmina Bay was spectacular – yet another incredible moment in Antarctica.

The 24-km wide bay was discovered by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897-99 led by Adrien de Gerlache and is named for Wilhelmina, Queen of the Netherlands, who reigned from 1890 to 1948. The krill-rich waters of the bay are surrounded by steep cliffs full of snow and glaciers.

A Humpback whale diving in Wilhelmina Bay. The pattern on the underside of their fluke is a unique identifier.

While in the bay, we did a sea excursion, spending an exciting afternoon surrounded by pods of huge Humpback whales, which could surface anywhere, at any time.

On one occasion, one of the zodiac drivers had to do a quick reverse in order to avoid being hit by a surfacing whale, who emerged directly beneath his boat.

The driver of this zodiac quickly reversed when he noticed bubbles surrounding his boat, narrowly avoiding impact with a surfacing 30,000-kg Humpback whale.

The humpback gets its name from its habit of raising and bending its back in preparation for a dive, thereby accentuating the hump in front of the dorsal fin.

A diving Humpback whale in Wilhelmina Bay.

The diet of this giant (adults can weigh up to 30,000 kg) is tiny plankton, krill and fish, with adults consuming up to 2,500 kg of food each day. In order to gather such large quantities of what is very small prey, the whales employ a technique known as ‘bubble net‘ feeding.

Polar Plunge!

Fact: The temperature of Antarctic seawater during the summer hovers just below freezing at -0.8 to 0 degrees Celsius/ 31.8 to 32 degrees Fahrenheit. The water doesn’t freeze due to its salt content.

With a safety harness fitted, I’m ready to make my Polar Plunge into the icy waters of Wilhelmina Bay.

After our whale watching, it was time for another highlight of our expedition – the polar plunge!

The deep waters of Wilhelmina bay are full of humpback whale pods and it was here that we would immerse ourselves, for the briefest of moments, into the freezing Antarctic seawater.

So graceful! The deep, freezing water of Wilhelmina Bay is the perfect place for a Polar Plunge.

As a precaution against sudden shock, a safety harness is mandatory when doing the plunge. The sensation of suddenly hitting freezing water is truly shocking and I was very quick to climb the ladder back onto the ship, at which point I made a dash to the nearest hot shower.

Wow! That’s cold! The Polar Plunge is certainly an invigorating experience.

Of the 180 passengers, several dozen of us took part in this slightly crazy activity, with many participants adding a personal flair to his or her water entry.

Day 10 – AM: Graham Passage

Worth getting out of bed for this! An early morning view of the Graham passage from the bow of the Ocean Diamond.

On the morning of day 10, we awoke to the best weather of the entire trip and jaw-dropping views of the Graham passage (64°24′S, 61°31′W).

Part of the Danco coast, Graham Passage is a narrow channel that separates Murray Island from the west coast of the Antarctic peninsula – Graham Land.

A Zodiac in the Graham passage is dwarfed by the towering peaks of Graham Land.

First discovered by the crew of the whaling boat, the Graham, in 1922, the passage affords spectacular views of Graham Land which is characterised by a heavily glaciated, mountainous, frozen coastline which is mostly inaccessible.

An early morning Zodiac sea excursion in the Graham passage.

Our morning excursion would be a Zodiac ‘sea excursion’ in which we would be treated to incredible views of Graham Land, and a sighting of our first (and only) Leopard Seal, who was lazing about on an ice floe.

A Leopard seal relaxing on an ice floe in the Graham passage.

If there’s an apex predator in Antarctica, then it’s the Leopard seal (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information).

This mean, lean, killing machine is blessed with a generalised diet (penguins, seals, krill, fish and anything else really) but also few predators, with the Orca (Killer) whale being the only natural predator.

The Leopard seal, such as this one in the Graham passage, is a powerful and aggressive predator, whose diet includes penguins and seal pups.

The Leopard seal is perhaps best known for its reptilian-like head and massive jaws which allow it to be one of the top predators in its environment. It is the second largest species of seal in Antarctic, after the Southern Elephant seal.

Despite his seeming grin, the Leopard Seal is the bad boy of the seal world and is the dominate predator in places like the Graham passage.

The ends of a leopard seal’s mouth are permanently curled upward, creating the illusion of a smile or menacing grin. Maybe knowing they sit at the top of the food chain is reason enough to smile!

A Crabeater seal basking in the morning sun on an ice floe in the Graham Passage.

Despite the presence of their number one predator, there were plenty of Crabeater seals in Graham passage. No doubt, they were keeping a watchful eye on the Leopard seal as they basked in the sunlight on nearby ice floes.

A view of the mountainous Antarctic peninsula from the Graham passage.

Day 10 – PM: D’Hainaut Island

A view of the ‘Ocean Diamond’ moored in Mikkelsen Harbour and the Argentine refuge Refuge Caillet-Bois on D’Hainaut Island.

From the Graham passage, we cruised north to D’Hainaut Island which lies in the middle of Mikkelsen Harbour, a 3-km wide bay, lined with ice cliffs, indenting the south side of Trinity Island, in the Palmer Archipelago.

Following lunch, we made a land excursion to tiny D’Hainaut Island (less than 1 square km) which is home to a small Argentine refuge, Refuge Caillet-Bois, which was surrounded by breeding Gentoo penguins.

Remnants of a past era – the remains of an old whaling boat lie among discarded whale bones on the beach at D’Hainaut Island.

The sheltered waters of Mikkelsen harbour once offered a safe place for whalers to live and process slaughtered whales. Today, there’s a large pile of whalebones and a whalers’ wooden, water-boat located on the northeast shore of the island.

Discarded whale bones litter the beach on D’Hainaut Island.

One of the highlights of our excursion to D’Hainaut Island was the sighting of a Weddell seal. The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expeditions led by British sealing captain James Weddell to the area of the Southern Ocean now known as the Weddell Sea.

A Weddell Seal relaxing in the snow on D’Hainaut Island.

Able to dive to depths of 600 metres for up to an hour, Weddell seals spend much of their time below the Antarctic ice, using their teeth to carve breathing holes in moving ice. They have the southernmost range of any seal, but find the chilly waters rich with the prey they seek. Weddell seals eat an array of fish, bottom-feeding prawns and crustaceans.

A Weddell Seal on D’Hainaut Island.

Weddell seals are the second most abundant species of seal in Antarctica, after the crabeater seal, with an estimated population of more than 1,000,000 individuals.

A curious South polar skua investigates my camera bag on D’Hainaut Island.

D’Hainaut Island is a popular breeding ground for the South polar skua which is always curious and mischievous. The skua is widespread throughout coastal regions of Antarctica, with its diet consisting of fish and krill, though penguins, as eggs, chicks and carrion form a variable but sometimes exclusive supplement depending on location.

Fish may be obtained by stealing it from other birds, particularly gulls, while anything else, even my camera bag, will be investigated by this curious creature.

Gentoo penguins on D’Hainaut Island travel along a Penguin Highway.

D’Hainaut Island is a busy breeding ground for Gentoo penguins, with so many on the island, that they have created deep ruts (known as penguin highways) through the snow as they waddle to and from the sea.

Day 11 – AM: Trinity Island

Chinstrap penguins, such as these on Trinity Island, are named for the narrow black band under their heads.

On the morning of day 11 we made one last sea excursion at Trinity Island, where we saw Chinstrap Penguins and our only Antarctic fur seals (see the ‘Wildlife‘ section below for more information on both of these species).

A Chinstrap penguin on Trinity Island, airing its flippers after emerging from the sea.

Weighing in at 3.5 to 5.5 kg, the Chinstrap penguin is distinguished by the narrow band of black feathers which extends from ear to ear, just below the chin and the cheeks. Males and females look similar but males are larger and heavier than females.

Chinstrap penguins on land often toboggan — laying on their stomachs, propelling themselves by their feet, and using their flippers.

Chinstrap penguins, such as this one at Trinity Island, are closely related to the Gentoo and Adélie penguins.

Closely related to the Gentoo and Adélie penguins, Chinstrap penguins breed mainly in the northern, warmer regions of the Antarctic Peninsula and on islands in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Chinstrap penguins feed mainly on krill and fish and are considered near-shore feeders, feeding close to their breeding colonies. They catch prey by pursuit-diving, using their flippers to ‘fly’ through the water.

An Antarctic fur seal, basking in the (relative) warmth of the more northerly Trinity Island.

Once close to extinction, Antarctic fur seals, also known as the Southern fur seal, are restricted mainly to the sub-Antarctic islands, with 95% of the world’s population being found on the island of South Georgia. The only ones we saw during our voyage were on Trinity Island, the most northerly, and warmest, of our destinations.

The Antarctic fur seal, such as this one at Trinity Island, is the only ‘eared’ seal in Antarctica.

Antarctic fur seals are the smallest seals. Closely related to sea lions, they able to walk on all fours. Each have teeth, whiskers, ears and thick fur, similar to the coat of a dog. Instead of having layers of fat, like other seals, Antarctic fur seals rely on their thick coat for warmth.

Antarctic fur seals, such as this cute guy on Trinity Island, have made a remarkable comeback after being close to extinction.

In the 1700’s and 1800’s, Antarctic fur seals were almost completely wiped out by sealers. Captain James Cook visited South Georgia Island (the main breeding ground) in 1775 and reported that there were a great many seal’s present. This led to sealers setting sail to bring back the pelts which were made into ladies’ coats.

By 1822, the Antarctic fur seal was virtually extinct on South Georgia. Almost hunted to extinction, the Antarctic Fur Seal has made a comeback with current population estimates of around 4 million.

Day 11 – PM: Antarctica to Ushuaia

On our last day in Antarctica, a spectacular sunset bid us a final farewell.

On the afternoon of day 11, we started the long journey back across the Drake passage to Ushuaia, which lies 1,095 km to the north-west of Trinity Island.

An iceberg glows in the setting sunlight as we commence the long journey from the Antarctic peninsula, across the Drake passage, back to Ushuaia.

Icebergs glow in the setting Antarctic sun.

Day 12-13: Antarctica to Ushuaia

On days 12 and 13 we sailed back across the Drake Lake – yes – it was that calm! Strange to see this body of water, which is famous for its raging weather, as smooth as a lake.

As a result of our smooth voyage, we arrived at the entrance to the Beagle channel way ahead of schedule and had to wait half a day for our allocated appointment with the Argentine pilot who would escort us through the channel and back into Ushuaia port.

Day 14: Ushuaia Arrival

Early morning arrival back at Ushuaia port in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina.

Early, on the morning of day 14, we docked at a sleepy Ushuaia where we cleared customs and immigration (although technically we had never left Argentina), said goodbye to new friends and went our separate ways.

An unforgettable experience which provided a lifetime of memories!

Wildlife

Penguins of Antarctica

Did you know…. the 24th of April each year is designated “World Penguin Day“.

There are a total of 17 different species of penguins on the planet – all of them resident in the Southern hemisphere.

While many penguins call Antarctica home, a greater number prefer to inhabit the warmer sub-Antarctic islands, the southern reaches of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and South America.

Thanks to the cold Humboldt Current, penguins can even be found on the Equator in the Galapagos Islands.

All penguins are flightless birds with wings that have been modified into paddle-like flippers and streamlined bodies which are a perfectly adapted for life in a marine habitat.

Antarctica is home to 5 different breeding species:

- Adélie Penguin

- Chinstrap Penguin

- Emperor Penguin

- Gentoo Penguin

- Macaroni Penguin

Of the five different species, I saw four during my trip – Chinstrap, Adelie, Emperor and Gentoo.

What’s with the tuxedo look?

A Gentoo penguin at Port Lockroy. The ‘tuxedo’ colours of penguins serve as ‘counter’ camouflage, allowing them hide from predators while in the water.

Most penguins sport a very fancy looking pelt which resembles a tuxedo with the dorsal side, back and head being black and the belly being white. What’s with the look?

The feather pattern is a form of camouflage called counter-shading, which is used to help them hide from predators while in the water. Viewed from above, their black back and head blends in with the dark seafloor. When viewed from below, their white belly blends into the bright surface of the water.

Adélie Penguin

An Adélie penguin, airing his flippers on Detaille island.

The most southerly (and most numerous) of breeding Antarctic penguins – Adélie penguins were discovered in 1840 by scientists on a French Antarctic expedition led by explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, who named the penguins after his wife – Adéle.

Closely related to the Gentoo and the Chinstrap, the Adélie inhabit the most southern reaches of the Antarctic peninsula and were the first we saw upon arrival in Antarctica.

Recent satellite surveys have led to revised population figures for the penguin with an estimated six million on the peninsula – an increase of more than 50% over previous figures.

The penguins inhabit large breeding colonies which are very smelly, loud, raucous and busy affairs. Like the Chinstrap and Gentoo, they build their nests using small pebbles on raised ground (prevents flooding when the snow and ice melt) and give birth to two young.

During our visit, there were plenty of chicks vying for the attention of their (feeding) parents.

Chicks are at risk of being snatched by predatory South polar skua’s (see ‘Birds of Antarctica‘ below) who also feed on unhatched eggs. Like other penguins, the Adélie feed mainly on krill but are themselves a valuable food source for Leopard Seals, Sea Lions, Orcas, and Sharks.

Chinstrap Penguin

Chinstrap penguins, such as this one on Trinity Island, get their name from the fine black band of feathers which runs, from ear to ear under their chin.

Chinstrap penguins get their name from the fine black line which runs, from cheek-to-cheek, across their white face.

Closely related to Gentoo and Adélie penguins, during our trip the Chinstrap’s were busy maintaining their nests, incubating their eggs (normally two) and looking after new-born chicks.

Like other penguins, their nests are built from small pebbles which they arrange in a roughly circular pile. The Chinstrap has a similar diet and faces the same predatory threats as the Adélie and Gentoo penguins.

Emperor Penguin

Emperor penguins, such as this one at Crystal Sound, are easily distinguished by their large size and the yellow patches on either side of their face.

The name says it all! The Emperor penguin is the most majestic, the tallest (up to 122 cm/ 48 in) and the heaviest (from 22 to 45 kg / 49 to 99 lb) of all penguins and is found only in Antarctica.

It is the undisputed heavyweight of the penguin world! Apart from its stature, the penguin is easily distinguished thanks to the broad yellow patches on each side of its head. To see such a majestic creature in the wild is something truly special.

The Emperor is the only species that breeds during the savage Antarctic winter, and it’s not uncommon for them to trek over a hundred kilometres inland to reach their breeding colony.

Once at the colony, the female lays a single egg, which is then incubated by the male who rests the egg on his feet (to keep it off the freezing ground) for 65 days (actually it’s one long, cold period of night at this time of year) while the female returns to the sea to feed.

During this period the male does not eat and will typically lose 40% of his body weight. The female, now full of food, returns to feed the newly-born chick while the male dashes to the sea to satisfy his dying hunger.

With a diet that consists primarily of fish and krill, the Emperor has a life span of about 20 years.

Gentoo Penguin

Gentoo penguins, such as this daredevil at Port Lockroy, are the 3rd-largest species of penguin, after the Emperor and King.

In an otherwise monochrome landscape, the Gentoo penguin provides a much-appreciated splash of colour.

With its flamboyant reddish/ orange-coloured beak and peach-coloured feet, the Gentoo penguin stands out against the usually drab-coloured landscape. The Gentoo is the 3rd-largest species of penguin after the Emperor and King.

Like their cousins, the Chinstraps, the Gentoo penguins were busy during our trip with all the rituals associated with the breeding season.

Also like the Chinstraps, their nests are built from small pebbles which they arrange in a roughly circular pile.

The pebbles are jealously guarded and their ownership can be the subject of noisy disputes between individual penguins. Often a male will gain ‘favour’ from a female by offering her a nice stone – which he would have stolen from a neighbouring nest.

This of course leads to disputes and a whole lot of noise. The Gentoo is not shy, is very mischievous and entertaining – a real pleasure to spend time observing.

During the breeding season the even more mischievous and opportunistic South polar skua preys on breeding Gentoo colonies, stealing unhatched eggs or snatching baby chicks.

Seals of Antarctica

Although there are 35 species of seals (or more correctly – Pinnipeds) in the World, only six species inhabit Antarctica:

- Antarctic Fur Seals

- Crabeater Seals

- Leopard Seals

- Ross Seals (rarely seen as it inhabits remote ice shelves)

- Southern Elephant Seals

- Weddell Seals

Seals are categorised into three families:

- True seals (this includes all Antarctic seals except the Fur Seal)

- Eared seals (common to most zoos and includes the Fur seal)

- Walruses (only found in the Arctic).

We saw five different species during our trip:

Antarctic Fur Seal

Antarctic Fur seals, such as this one at Trinity Island, prefer the warmer, more northern extremes of the Antarctic peninsula.

You can excuse the poor Antarctic fur seal for having such bad manners (they have been known to bite humans without provocation) but we did nearly hunt them into extinction.

At one point, their total population was reduced to a few thousand. Antarctic fur seals were placed under protection at the beginning of this century and have made a remarkable recovery.

Normally found in more northern parts of the Antarctic Peninsula and the sub-Antarctic islands, we were lucky enough to see just a few on Trinity Island on the our last in Antarctica.

Crabeater Seals

A Crabeater seal, relaxing on an ice floe in the Graham passage, enjoys the early morning sun.

The most common seal in Antarctica, the Crabeater accounts for over half of the world’s seal population with an estimated population of 30 million.

Despite their name, Crab-eaters mainly eat krill but are themselves preyed upon by Orca whales and the aggressive Leopard seal, which will attack young pups. Most Crab-eaters bear deep bodily scars from battles fought with Leopard seals.

Misnamed by early Antarctic whalers and sealers, the Crabeater seal doesn’t eat Crabs but rather Krill, which always leaves a blood stain around their mouths.

Each day we saw plenty of Crabeater seals who spend most of their time lazing around on ice floes. Feeding Orcas like to bump the ice floes in order to knock the seals into the water.

Leopard Seal

A Leopard seal, relaxing on an ice floe in the Graham passage.

A lean, mean, fighting machine – the aggressive, powerful Leopard Seal sits at the top of the food chain in the seal world. Easily identified by its reptilian-like head, the Leopard seal is an apex Antarctic predator, feeding on everything from seals, penguins, fish and krill.

With worldwide population (all in the Antarctic region) figures ranging from 220,000 – 440,000, the seals are not too common. During our entire trip we saw one lone seal lazing about on an ice floe.

Southern Elephant Seal

A Gentoo penguin narrowly escapes being crushed by a female Southern Elephant seal on Petermann island.

Named for the male’s trunk-like proboscis (nose) and weighing in at a hefty 3,600 kilos (7,900 pounds), these are the big daddies of the seal world.

There is no bigger seal than the Southern Elephant Seal. Longer (4.5 metres/ 15 feet) and heavier than the average family car, these guys eat a whole lot.

In order to satisfy their huge appetites, Southern Elephant Seals can dive to depths in excess of 2,000 metres/ 6,500 feet and can remain underwater for up to two hours.

The lucky (or maybe unlucky) males live in harems which can include up to 50 females. Breeding colonies can become cramped affairs which small pups often becoming crushed under the weight of adult seals.

Weddell Seal

A Weddell seal relaxing on D’Hainaut Island.

Unlike other seal species, Weddell Seals prefer to lie on shoreline snow and ice rather than floating ice floes where they could be preyed upon. They prefer to stay a safe distance from their main predator – the Orca.

During the winter months, Weddell’s must maintain diving/ breathing holes in the ice in order to feed. Feeding primarily on fish, Weddell seals can dive in excess of 300 metres / 1,000 feet in search of food.

To make these long dives possible, they carry five time the amount of oxygen in their blood as humans. To get the most from this, Weddell’s slow their heart rate and limit blood circulation to vital organs such as the brain, kidneys, and liver.

Whales of Antarctica

The food-rich waters of Antarctica attract a large number of feeding whales from Right, Blue, Sei, Humpback, Minke, Fin, Sperm and Killer.

Humpback Whales

A Humpback whale, diving in Wilhelmina Bay.

In Wilhelmina Bay (aka Whale-mina Bay), we had the opportunity to get very close to a number of feeding pods of Humpback Whales.

Wilhelmina Bay has a well-deserved reputation for whale watching and, on the day we visited, we found ourselves surrounded by multiple pods of these huge creatures, who, more than once, came in very close proximity to our small, exposed zodiacs.

The fluke of a diving Humpback whale in Wilhelmina Bay.

This behaviour is not instinctual, it is learned with the whales using vocalisations to communicate to one another in order to effectively and efficiently execute the bubble net in order for them all to feed. The technique involves the pod circling below a school of prey, while exhaling out of their blowholes, producing a wall of bubbles which corrals the fish into the centre of the circle.

The captured fish become disoriented then one whale will sound a feeding call, at which point all whales simultaneously swim upwards with mouths open to feed on the trapped fish. On its way to the surface, the humpback can collect up to 57,000 litres (15,000 gallons) of seawater in its mouth, which it then strains out through its baleen plates, allowing it to swallow it’s catch.

We ventured out into the bay in our Zodiac and made a bee-line for the first pod we saw surfacing. The pod had a new member – a young calf – and was too busy feeding to be disturbed by our presence. Observing all the rules, we kept our distance. The whales would disappear beneath the calm waters of the bay – then, sometime later, a ring of bubbles would start to appear on the surface, then the calm would be shattered when a giant feeding Humpback came shooting up out of the water with its mouth wide open.

A diving Humpback whale in Wilhelmina Bay.

While we kept our distance, the whales know no boundaries and will create a bubble net wherever the prey is concentrated – at times this can be right under your little zodiac. While we were waiting for one pod to surface, the zodiac next to ours was suddenly surrounded by bubbles. Seeing this the driver quickly put the boat into reverse and got out of the way just as a 30,000 kg missile came shooting out of the water. It was very close!

At one point we were surrounded by four feeding pods, with whales surfacing and diving all about us. We were busy taking photos and watching out for the bubbles.

I’ve had the opportunity to do whale watching in various places around the world but there’s nothing like whale watching in Antarctica. From the stunning scenery, the quiet, remote isolation and the fact that you can get so close to such magnificent wildlife – every day in Antarctica provides another lifetime memory.

Birds of Antarctica

Besides Penguins (yes – they are birds!), Antarctic is home to many other birds. Some of the birds we encountered on the trip included:

South polar skua

Gentoo penguins on Cuverville island, defending their nests against an attack by a South polar skua.

The South polar skua can best be described as an avian pirate. These birds are very mischievous, cheeky and opportunistic and will seize almost anything – one once tried to seize my 10 kg camera bag while it was on the ground.

The skuas favourite feeding grounds are the numerous penguin colonies, where they easily snatch unhatched eggs and new-born chicks.

Kelp Gull

A Kelp Gull on Detaille Island.

An omnivore and an opportunistic feeder, despite their name the diet of the Kelp Gull is not limited to kelp but also includes live Right Whales. Yes – the gull has been observed using its beck to peck down several centimetres into the skin and blubber, often leaving the whales with large open sores. Nasty!

Antarctic Tern

An Antarctic Tern flying over the Yalour Islands.

The Antarctic Tern is easily spotted thanks to its bright red beak. The tern breeds in Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic islands, with a diet of fish which it hunts along coastal areas.

Snowy Sheathbills

A Snowy Sheathbill in Antarctica.

Otherwise known as the Paddy, the Snowy Sheathbill is one of two types of species of sheathbill and is usually found on the ground.

It is the only land bird native to the Antarctic continent. Lacking webbed feet, the sheathbill feeds on land, stealing krill and fish from penguins and sometimes eating penguin eggs and young penguin chicks.

Despite looking plump and dove-like, but are believed to be similar to the ancestors of the modern gulls and terns.

Conclusion

A trip to Antarctica is an unforgettable experience. From the remoteness of the continent to the stupendous, breath-taking scenery that surrounds you every day, to the amazing wildlife interactions to the experience of being part of an expedition ship – it’s a memory that will stay with you forever.

While the cost of joining an expedition may seem high – I felt at the end of the trip that the money I paid was very reasonable. I was provided comfortable accommodation onboard a well-appointed, luxury expedition ship, which was operated by a crew of 100, professional, competent staff members from all corners of the globe.

We were fed amazing multi-course meals, three times daily, were provided with a constant supply of snacks between excursions and were provided with nightly entertainment from members of the expedition team.

Also included was the expertise and knowledge of the various expedition team members, most of whom provided presentations during the voyage and expert commentary and insights when on excursions.

Would I do it again?

Yes – and if you have the means to make such a trip, I would highly recommend that you do so – at least once in your life!

That’s the end of my Antarctica Travel Guide.

Safe Travels!

Darren

Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica

Follow me on Instagram:

[instagram-feed feed=1]

AAAtarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide

Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide Antarctica Travel Guide

Author: Darren McLean

Darren McLean is an Australian, full-time, digital nomad who has spent 37 years on a slow meander around the globe, visiting all seven continents, 192/ 193 UN countries and 245/ 251 UN+ countries and territories.

He founded taste2travel to pique one’s curiosity and inspire wanderlust.